The Pan-African Data Project History & Futures

Where we have been, and where we are going

Phase I (2019-2022)

The Pan-African Data Project emerged from an earlier project, the Power Players of Pan-Africanism, a collaboration between Roopika Risam, who was then an associate professor at Salem State University, and Jennifer Powers, an MEd candidate in English education. Powers was also participating in the Digital Scholars Program, an opportunity to pursue digital humanities research that Risam founded along with Salem State’s archivist Susan Edwards and digital initiatives librarian Justin Snow. Risam was broadly interested in developing digital humanities research tools to support students and researchers in Black diaspora studies, while Powers was invested in the pedagogical possibilities of data literacy, particularly for introducing high school students to topics and people underrepresented in K-12 curricula. Together, in fall of 2019, Risam and Powers hatched a plan for research, data collection and curation, and data modeling: create a dataset that identified events — conferences, meetings, symposia — related to Pan-Africanism and the people who took part in them, inspired by Risam's work developing the Global Du Bois project. During the spring of 2020, they were joined by Hibba Nassereddine, also an MEd candidate in English education and Digital Scholars Program participant. Over the course of a year, Risam, Powers, and Nassereddine conducted extensive primary and secondary source research to identify Pan-African events and their participants. In doing so, they confronted many of the challenges inherent in working with data on understudied historical movements — such as incomplete archives, inconsistent records, and dispersed documentation across continents and languages.

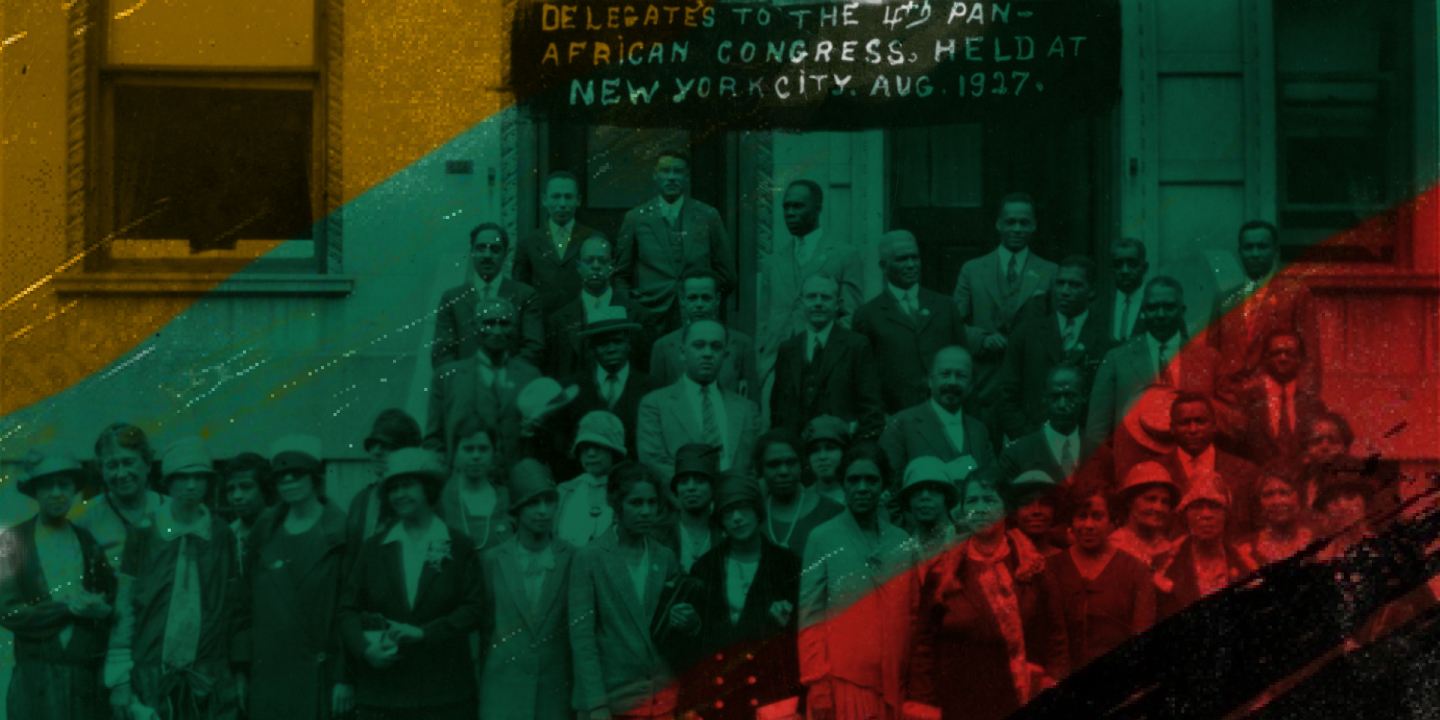

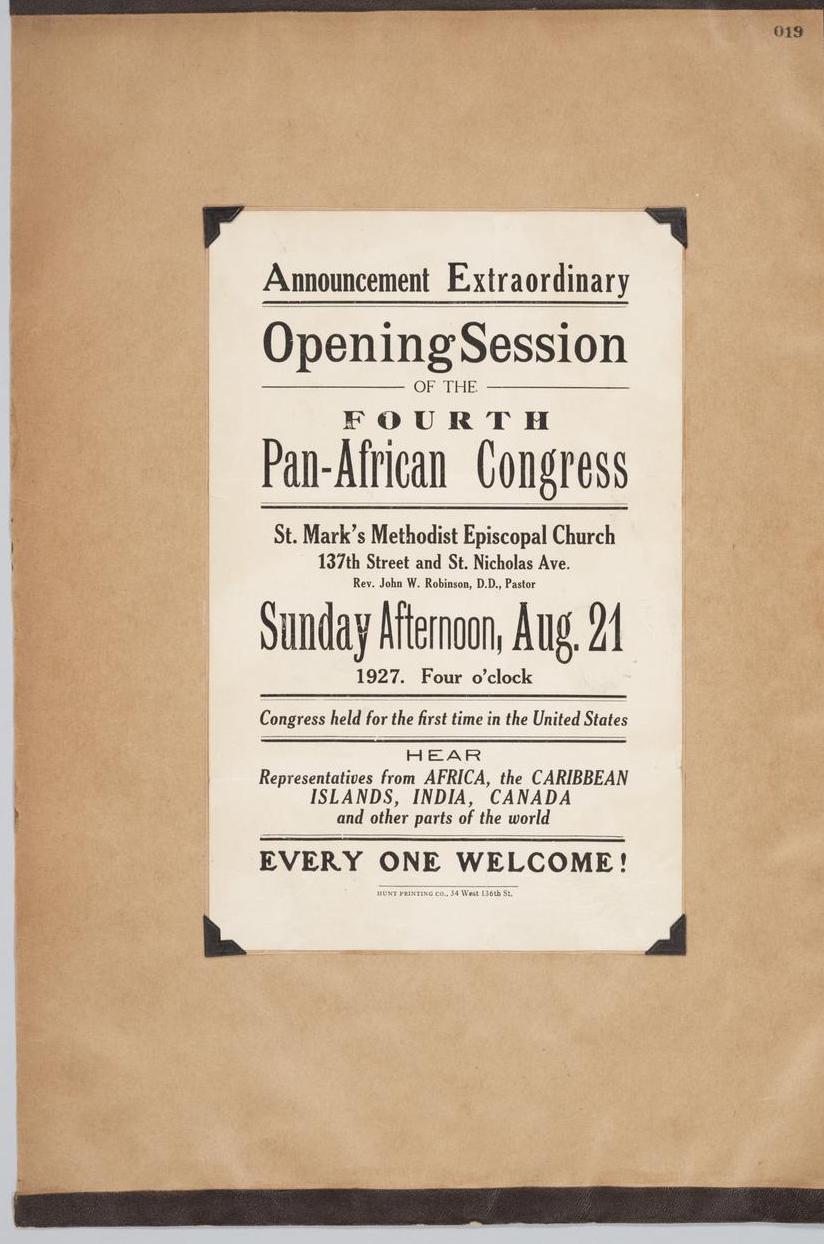

Announcement for Fourth Pan-African Congress, New York, 1927. Public domain.

This exploratory phase also included early data visualization experiments using Google Sheets, Tableau, and Gephi to prototype ways of representing networks, timelines, and geographies of Pan-Africanism. Initially, the team hoped that network analysis would reveal new insights about the Pan-African Movement — perhaps identifying attendees of Pan-African events who had been overlooked, expanding the familiar narratives centered on figures like W. E. B. Du Bois and Kwame Nkrumah. However, when they generated the networks, the results largely reproduced what was already known, foregrounding the same celebrated figures. Because Du Bois was present at the highest number of events — seven of the nineteen the team was focused on — and most people had only attended one, the network visualization amounted to little more than a giant hairball. The team had been too enthusiastic about the possibilities of network analysis and recognized that it as not a viable way of exploring the datasets. They knew, however, that the data itself was valuable, even if the methods they were using were not producing results that offered the deeper insights on Pan-Africanism that they had hoped to find.

A session of the Pan-African Congress, Paris, February 19-22, 1919. Public domain.

The results of their work included datasets for 19 events committed to GitHub and a co-authored article, “Data Fail: Teaching Data Literacy with Digital Humanities,” published in the Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy in 2020. The article was voted 2nd runner up in the Digital Humanities 2020 awards. In addition to credit for their work on the project and the article, Powers and Nassereddine received graduate credit for independent studies, paid for by the districts where they were simultaneously student teaching.

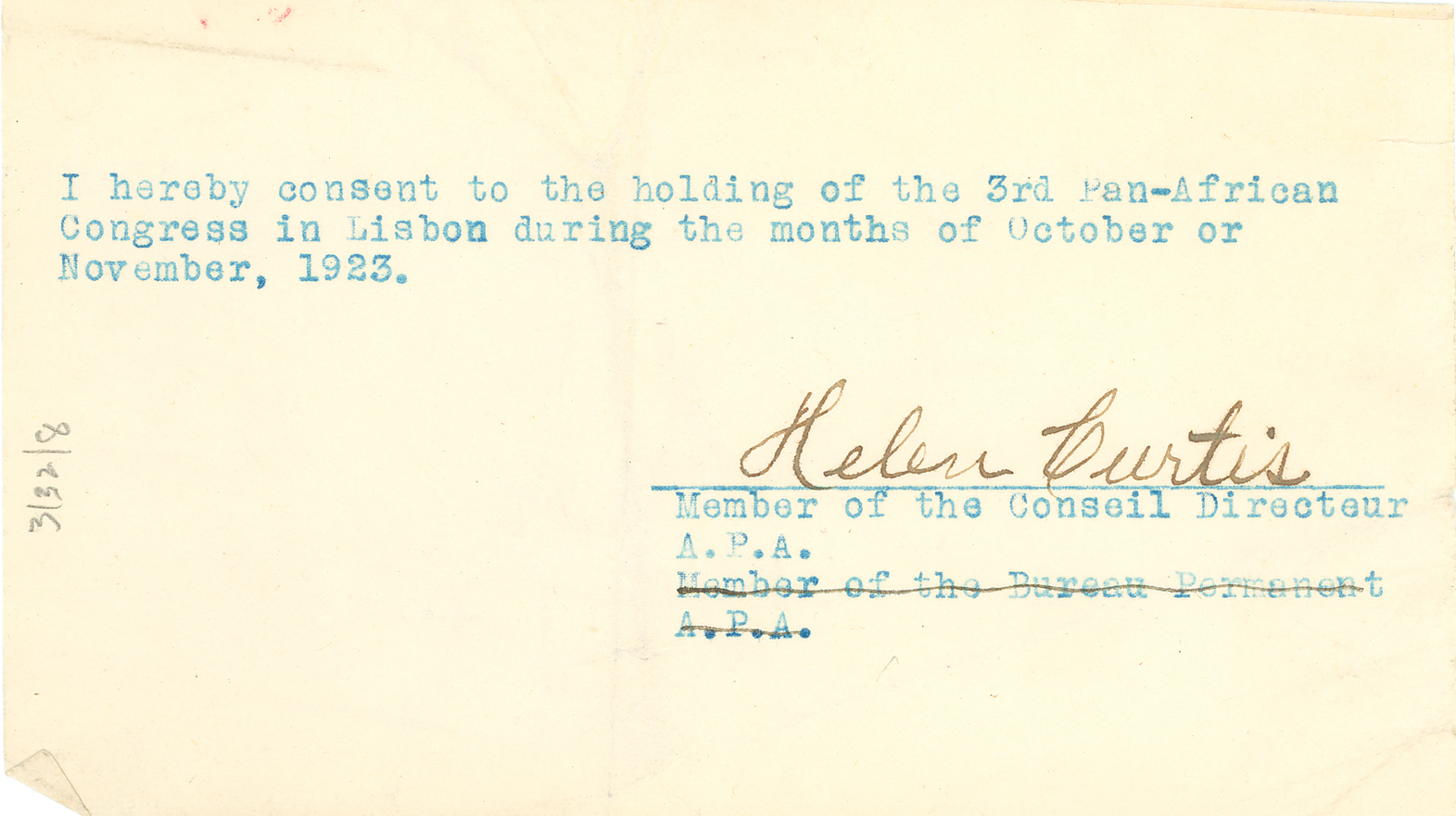

Helen Curtis's agreement to hold the Third Pan-African Congress in Lisbon, 1921. Public domain.

Phase II (2022-2025)

When Risam moved to Dartmouth in 2022, she wanted to build on the earlier team's work. The idea of identifying “power players” ultimately felt limiting for understanding the collective and relational nature of Pan-Africanism. Seeking new directions, Risam consulted Quinn Dombrowski, her collaborator on The Data-Sitters Club project, who encouraged her to think differently about what the data might reveal. Could it show how participation, presence, and encounter shaped the movement in less visible ways? This conversation led Risam to reimagine the project, to see it not as a blunt instrument to produce definitive, quantitative conclusions but as an interactive resource to support further research, surface unfamiliar names, and invite new interpretations of Pan-African history. She began planning for an interactive website that would allow researchers or anyone interested in Pan-Africanism to explore the data. Through her Digital Ethnic Futures Lab at Dartmouth (now the Creative and Critical Data Studio, co-directed with Dartmouth professor Jacqueline Wernimont), Risam brought on additional students to help her expand the original datasets into a new one that included organizations for the Pan-African Data Project (PADP). Nyashazadshe Jongwe, Vy Nguyen, and Ore James added gender for participants, which was instrumental to highlighting the vital role of women in Pan-Africanism. All Dartmouth students were compensated for their contributions.

Declarations and resolutions adopted by the Fifth Pan-African Congress, Manchester, 1945. Courtesy of the Working Class Movement Library.

Two fellowships that Risam held during the 2022-2023 academic year were significant for the PADP. Through the AADHum Scholars Program at the African American Digital Humanities Initiative at the University of Maryland, College Park, Risam had the opportunity to envision the future of the project, in conversation with Marisa Parham, Jeffrey Moro, and Andrew W. Smith. The folks at AADHum were particularly skilled at thinking through what the datasets could and could not show, and what visualizations might do (and talked Risam out of some terrible ideas!). A fellowship at Cambridge Digital Humanities, at the University of Cambridge, was equally valuable. Risam greatly benefited from conversations with Caroline Bassett, Leonardo Impett, and Siddharth Soni. She also connected with Cambridge professor Rachel Leow, who was part of the Afro-Asian Networks Research Collective. They discussed the challenges of Risam's research on Pan-Africanism and Leow and her collaborators' work on Cold War internationalism — and the intersections of both movements. As a result, Afro-Asian Networks agreed to share their data for the PADP, to give it a new life beyond the term of their grant, funded by the UK's Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). At Cambridge, Risam also met David Palfrey, a committed Wikipedian, and they discussed strategies for linked open data. Palfrey later added the project's data to Wikidata, with the goal of helping diversify content on Wikipedia.

A delegate addresses the crowd at the Fifth Pan-African Congress, Manchester, 1945 © John Deakin via Getty Images, used under license.

To build the PADP's website, Risam partnered with Performant Software Solutions, which works with humanities scholars to build tools for research and teaching. This decision was based on her long admiration for their commitment to open-source software. The PADP could adapt Performant's code and support new features for the site that would be available to other scholars. Risam worked with Jamie Folsom, Anindita Basu Sempere, Chelsea Giordan, Derek Leadbetter, Ben Silverman, Rebecca Black, and Camden Mecklem to develop the site and interactive visualizations. Specific features designed for the PADP include timelines, data exports, browser-based saved searches, custom data visualization embeds in posts, and static-site deployment, all of which can be re-used. Dartmouth graduate students Lethokuhle Msimang and Mikayla Walker collaborated with Risam to prepare the dataset for the backend FairData repository and to add Wikidata and VIAF identifiers. Risam also consulted with historian Amara Thornton of the Beyond Notability project on site development. The current version of the PADP launched in October 2025.

Members of the Second Pan-African Conference, Brussels, 1921. Public domain.

Plans for Phase III (2025-2028)

The PADP is an evergreen project, with new data continually added to the Events, People, and Organizations Explorers. We aim to increase granularity in the People Explorer by identifying individuals’ relationships to places; distinguishing between observers, delegates, and members of the press; and indicating connections among people. Planned improvements include enhanced faceted search — adding occupations and distinguishing among Pan-African, Afro-Asian, and Non-Aligned Movement events — as well as linking events with relevant organizations. Future expansions include Explorers for periodicals and educational institutions connected to Pan-Africanism and a French version of the site. We have more substantial plans that would require extramural funding, but this project is ineligible for federal grants in the U.S., where we are based, because of the Trump Administration's restrictions on funding for research that engages questions of race, colonialism, and historical inequity. We remain committed to sustaining and expanding the project through institutional partnerships and independent support, and we welcome collaborations.

Circular letter issued by the Pan-African Congress, Paris, 1919. Public domain.

Rights and Reuse

The Pan-African Data Project © 2025 by Roopika Risam et al. is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. We encourage reuse and remixing of the project and its data.

Citation

To cite this page, please use: Risam, Roopika, et al. 2025. "The Pan-African Data Project History & Futures." The Pan-African Data Project. https://www.panafricandata.org/en/pages/padp-history-futures/.