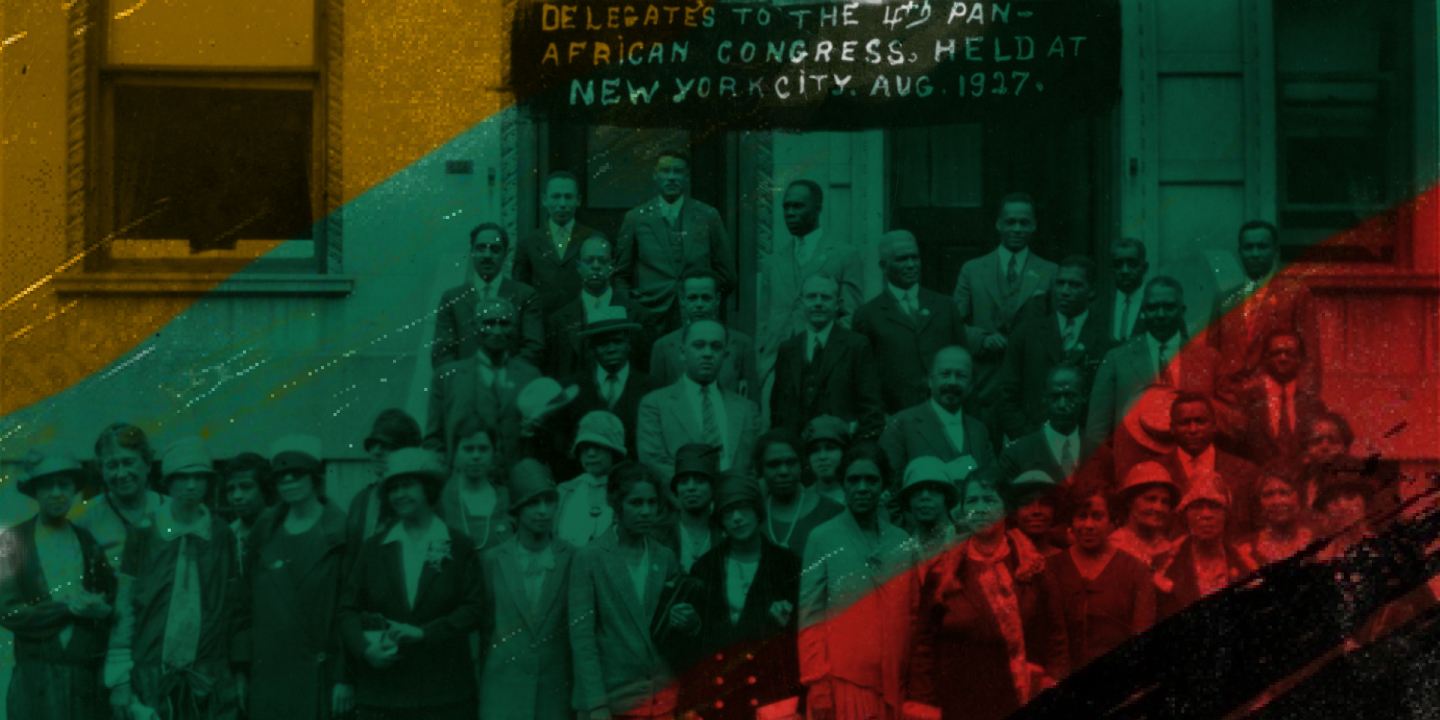

Pan-Africanism emerged at the turn of the twentieth century as a global network of ideas, activism, and solidarity linking Africa and its diasporas. Its origins lay in early gatherings — starting with the 1900 Pan-African Conference in London — where men and women alike, as intellectuals and organizers, challenged imperial domination and articulated a shared vision of Black freedom (Geiss 1974). Since its beginnings, Pan-Africanism has developed into a dynamic political and cultural movement, uniting campaigns for racial equality, self-determination, and economic justice from the Caribbean and the Americas to Europe and the African continent (Adi and Sherwood 2003).

Figures such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Kwame Nkrumah, George Padmore, and Nnamdi Azikiwe shaped the political and philosophical dimensions of Pan-Africanism alongside women whose intellectual and organizing work was equally foundational. Amy Ashwood Garvey, Jeanne Martin Cissé, Alice Kinloch, and Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, among others, advanced Pan-African thought through leadership in anticolonial movements, women’s associations, trade unions, and international diplomacy. Scholars have illuminated how these women’s activism and intellectual production expanded Pan-Africanism’s scope and connected it to Black feminist and diasporic networks (Reddock 2007; Blain 2018; Sheldon 2020). These women's writings, speeches, and organizing articulated visions of solidarity that linked gender equality to racial and national liberation, broadening the very meaning of freedom the movement pursued.

By mid-century, Pan-Africanism continued to thrive and intersected with broader currents of global liberation. Its principles resonated in the 1955 Bandung Conference, which brought together newly independent Asian and African nations to assert a Third World solidarity against colonialism and Cold War imperialism (Lee 2019). The ideas forged at Bandung helped lay the foundations for the Non-Aligned Movement, formally established in 1961, which united postcolonial states seeking to assert autonomy as the U.S. and the Soviet Union attempted to expand their spheres of influence during the Cold War (Dinkel 2018) and continues to forge multilateral relationships.

As more African nations won independence, Pan-African ideals began taking on new institutional forms — embodied in movements for continental unity, from the Casablanca and Monrovia blocs's respective visions of economic federation and gradual cooperation for new nation-states on the continent of Africa, to the founding of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963 (Biney 2011). Pan-African intellectuals and activists have also participated in Afro-Asian Writers’ Conferences and other forums where anticolonial thought has circulated through literature, art, and political theory (Edwards 2003).

These ideals continue through the African Union, founded in 2002 as the OAU’s successor, and through the Afro-Asian Peoples' Solidarity Organization, a non-governmental organization founded in 1957 that now has national committees in more than 90 countries in Asia and Africa. Together with other organizations, they uphold the vision of continental and global solidarity, collective sovereignty, and integration that has animated Pan-Africanism for more than a century.

In this wider context, Pan-Africanism is more than a call for transnational unity; it is a philosophy of relation that connects struggles across oceans and ideologies. It inspires visions of a decolonized world built on equality, cooperation, and shared humanity �— ideals that animate global movements for racial and social justice today.

References

Adi, Hakim, and Marika Sherwood. 2003. Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and the Diaspora since 1787. Routledge.

Biney, Ama. 2011. The Political and Social Thought of Kwame Nkrumah. Palgrave Macmillan.

Blain, Keisha N. 2018. Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Dinkel, Jürgen. 2018. The Non-Aligned Movement: Genesis, Organization and Politics (1927–1992). Brill.

Edwards, Brent Hayes. 2003. The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism. Harvard University Press.

Geiss, Imanuel. 1974. The Pan-African Movement: A History of Pan-Africanism in America, Europe, and Africa. Translated by Ann Keep. Africana Publishing Company.

Lee, Christopher J., ed. 2019. Making a World after Empire: The Bandung Moment and Its Political Afterlives. Ohio University Press.

Reddock, Rhoda. 2007. “Gender Equality, Pan-Africanism and the Diaspora.” International Journal of African Renaissance Studies 2 (2): 255–267.

Sheldon, Kathleen. 2020. “Women in Africa and Pan-Africanism.” In The Routledge Handbook of Pan-Africanism, 330–342. Routledge.